Rebecca Dekker

PhD, RN

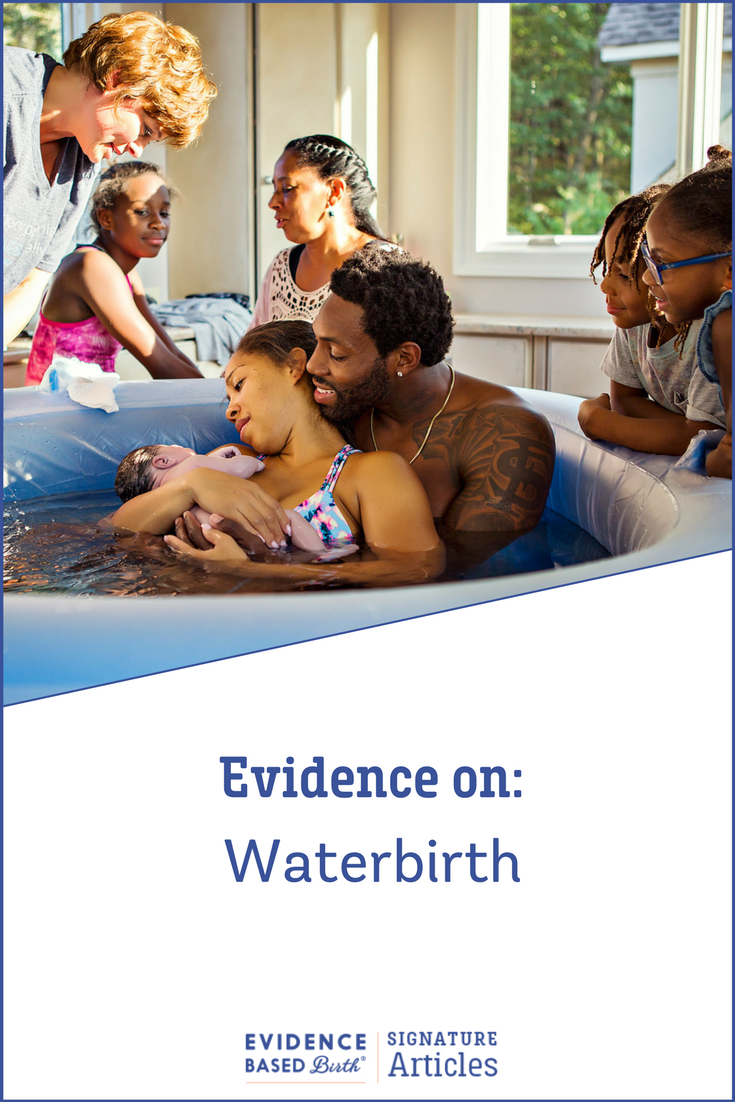

The Evidence on: Waterbirth

Originally published on July 8, 2014, and updated on February 14, 2024, by Rebecca Dekker, PhD, RN. Copyright Evidence Based Birth®. All Rights Reserved.

Please read our Disclaimer and Terms of Use. For a printer-friendly PDF, become an EBB Pro Member to access our complete library.

What is Waterbirth, and How is it Different than Water Immersion in Labor?

With water immersion in labor, you get into a tub or pool of warm water during the first stage of labor, before your baby is born. In a waterbirth, you remain in the water during the pushing phase and actual birth of the baby (Nutter et al., 2014a). The baby is then brought to the surface of the water after birth. With a waterbirth, the third stage of labor (when the placenta is born) may take place in or out of the water.

Researchers use the term land birth or conventional birth to refer to a birth in which the baby is born on dry land—not in a tub. And the word hydrotherapy can be used to describe the therapeutic use of water during labor and/or birth.

Waterbirth was first reported in an 1805 medical journal and became more popular in the 1980s and 1990s. The safety of water immersion during labor is well accepted (Cluett and Burns, 2018; Shaw- Battista, 2017). However, doctors and midwives, as well as health care professionals from various countries, often disagree on whether waterbirth is safe.

The purpose of this article is to provide you with the evidence on the safety and health outcomes of waterbirth. Then, we will share an overall summary of the pros and cons of waterbirth.

Before we dive into the evidence on waterbirth, it’s important to understand the impact that laboring in water—regardless of whether you give birth in the water—has on the labor process.

For example, one review of seven randomized trials with 2,615 participants looked at water immersion during labor (before normal land birth) and found that laboring in water posed no extra risks to birthing person or baby (Shaw-Battista, 2017). Water labor helped relieve pain, (leading to less use of pain medication), and led to lower anxiety, better fetal positioning in the pelvis, less use of medications to speed up labor, and higher satisfaction with privacy and the ability to move around.

By the very nature of waterbirth, a birthing person who births in water must also labor in water (for at least a few minutes, but sometimes for hours) prior to the actual waterbirth. Therefore, it is not possible to completely untangle the benefits of water immersion in labor from those of waterbirth. So, with this in mind let us now review what research has demonstrated about waterbirth outcomes.

Overview of Evidence on Waterbirth

In the early 2000s, the American Academy of Pediatrics released their first statement about waterbirth, in which they said: 1) there had not been research on waterbirth, 2) waterbirth posed only dangers for newborns, and 3) there were no benefits for mothers.

But the truth is that researchers from all around the world had been studying waterbirth for decades—and most of the research had found (and continues to find) that with low-risk births, the benefits of waterbirth greatly outweigh the risks.

Waterbirth research includes:

- Randomized, controlled trials—participants are randomly assigned (like flipping a coin) to give birth in water or give birth on land, and their outcomes are compared.

- Observational studies—researchers enroll people in the study, measure if they have a waterbirth or not, and compare health outcomes. These studies can be prospective (meaning people were enrolled in the study before they gave birth and followed forward in time) or retrospective (meaning researchers look back in time at births that already happened).

- Meta-analyses and systematic reviews—researchers combine data from many randomized trials and/or observational studies to look for overarching trends.

- Qualitative research—researchers use patient interviews or written text to describe what it feels like to have a waterbirth.

- Case studies—each case study contains a report of a single bad outcome (usually a very rare outcome).

Randomized Controlled Trials on Waterbirth

There have been five randomized trials on waterbirth, and so far, they show that waterbirth benefits include:

- Lower pain scores.

- Less use of pain medication during labor.

- Less use of artificial oxytocin (also known as Pitocin®).

- Shorter labors on average.

- Higher rate of normal vaginal birth (birth without the use of forceps, vacuum, or surgery).

- Higher rate of intact perineum (meaning the tissue between the vagina and rectum remains untorn and uncut).

- Less use of episiotomy (a surgical cut to the perineum).

- Greater satisfaction with the birth.

Three trials looked specifically at the effects of giving birth in the water (water immersion was not used earlier in labor) (Nikodem 1999; Woodward & Kelly 1994; Chaichian et al. 2009), and two trials included laboring in water plus waterbirth (Ghasemi et al. 2013; Gayiti et al. 2015).

Table 1: Randomized, controlled trials of waterbirth

Unpublished Student Thesis

One of these trials is an unpublished student thesis from South Africa (Nikodem, 1999). In this study, 60 people were randomly assigned to waterbirth and 60 people to land birth. There was no water labor—participants assigned to waterbirth entered the pool at the start of the pushing phase. The researchers found that the waterbirth group was more satisfied with their birth experience (78% vs. 58%), and that more people who had waterbirths said the pain was less than they expected it to be (57% vs. 28%). They found no difference in overall trauma to the birth canal between groups. The researchers defined trauma to the birth canal as labial tears, perineal tears, or injury to the vaginal wall.

Small Trial with Too Much Crossover

The second trial took place in the United Kingdom (U.K.) (Woodward & Kelly, 2004). In this study, only 10 out of 40 people who were assigned to the waterbirth group actually gave birth in water. Since most people didn’t stay in their assigned groups (this is called crossover), we cannot draw any conclusions from this study.

Small Trial that showed Waterbirth Benefits

The third trial took place in Iran. The researchers assigned 53 people to waterbirth and 53 people to land birth (Chaichian et al. 2009). Everyone in the waterbirth group gave birth in water. The researchers did not find any differences in newborn outcomes, but they found quite a few differences in maternal health outcomes between groups.

Waterbirth led to:

- A higher rate of normal vaginal birth (100% vs. 79.2%)

- A shorter active phase of labor (114 minutes vs. 186 minutes)

- A shorter third stage of labor (6 minutes vs. 7.3 minutes)

- Less use of artificial oxytocin (0% vs. 94.3%)

- Less use of any pain medications (3.8% vs. 100%)

- A 23% lower rate of episiotomy

- A 12% higher rate of perineal tears (reporting that most were mild tears)

There were no differences between groups in the length of the pushing phase of labor or the rate of breastfeeding.

After this trial from Iran was published, two more randomized trials have come out on waterbirth—one from Iran and one from China.

Largest Randomized Trial so far with 200 Participants

A 2013 Iranian trial (Ghasemi et al. 2013) randomly assigned 100 people to waterbirth and 100 people to land birth, making it the largest randomized trial ever done on waterbirth. In the end, 83 people ended up staying in the waterbirth group and 88 people stayed in the land birth group. It’s not clear why people left the study. This study was published in Persian, and we were able to get details thanks to volunteer translators (Personal correspondence, Clausen and Basati, 2017).

The study found that birthing people randomly assigned to the waterbirth group (all of whom labored in water) had a lower chance of needing a Cesarean later in labor compared to the land birth group (5% versus 16%). Participants in the waterbirth group reported less pain than the land birth group, but the researchers did not give any details on how pain was measured.

There was less meconium (baby’s first stool) in the amniotic fluid with waterbirth (2% versus 24%) and fewer low Apgar scores with waterbirth compared to land birth. An Apgar score is a test of how well the baby is doing at birth. A low Apgar score means that the baby may require more medical assistance.

Another Randomized Trial found Benefits to Waterbirth

A study that took place in China (Gayiti et al. 2015) randomly assigned 60 participants to waterbirth and 60 participants to land birth. Everyone who was randomly assigned to the waterbirth group gave birth in the water.

The researchers did not find any differences in newborn health outcomes between groups, but they found several maternal health benefits to waterbirth. Compared to the land birth group, the waterbirth group had a higher rate of intact perineum (25% vs. 8%). The waterbirth group also had a much lower rate of episiotomy (2% vs. 20%), and lower pain scores. The total length of labor was also shorter in the waterbirth group, by an average of 50 minutes. They did not find any difference in the amount of blood loss between groups.

What are the Limitations of these Randomized Trials?

In all these trials, there was no evidence of harm from waterbirth. However, these studies were too small to tell differences in rare health problems. Researchers estimate that there would need to be at least 2,000 people in a waterbirth trial to see at least two rare events occurring (Burns et al. 2012). In one Australian study, only 15% of low-risk research participants said they would be open to being randomly assigned to a waterbirth or land birth (Allen et al. 2022). This means researchers would need to approach 13,000 laboring people to have the 2,000 needed for a waterbirth randomized trial.

Randomized, controlled trials are often considered to be the “gold standard” in research. But when studying an intervention like waterbirth, it can be very hard to carry out a large, randomized, controlled trial. Some birthing people feel very strongly about waterbirth and are not willing to be randomly assigned to waterbirth or land birth. Others may be assigned to have a waterbirth, but then must leave the tub early for some reason.

Because large, randomized trials are unlikely to be published in future due to these constraints, we must turn to other types of evidence about waterbirth. In observational (non-randomized) studies, researchers do not attempt to control who gives birth in the water versus on land, but they record where people choose to give birth and measure their health outcomes.

In the next section, we will look at large analyses where they combined data from randomized trials and observational studies.

Table 2: Meta-Analysis on Randomized Trials and/or Observational Studies on Waterbirth

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Since 2009, there have been seven systematic reviews or meta-analyses, where researchers combined research from randomized trials and/or observational studies on waterbirth. For a summary of their findings, see Table 2.

As time has gone on, researchers have been able to include more and more studies in these meta-analyses, giving us lots of information about the safety of waterbirth.

The largest, highest-quality, and most important review on waterbirth was published by Burns et al. in 2022. This review included 36 studies (25 of which examined waterbirths) from hospital and community birth settings from the year 2000 through 2021, resulting in 157,546 participants in the analysis.

The researchers found that laboring and/or giving birth in the water was associated with the following health results compared to no water immersion:

- Less use of Pitocin® to speed up labor.

- Less use of injectable opioids for pain management.

- Less use of epidurals.

- Reduced pain levels.

- Higher rates of intact perineum (positive outcome), but only in obstetric settings; in midwifery settings there were no differences between groups.

- Lower rates of episiotomy.

- Lower risk of postpartum hemorrhage.

- Lower rates of maternal infection.

- Higher rates of maternal satisfaction.

And there were no differences between the laboring and/or giving birth in water group vs. the standard care group with regard to:

- Rates of amniotomy (artificial breaking of the waters).

- Rates of Cesarean (but Cesarean rates were very low overall; average of 3.6%)

- Shoulder dystocia.

- Obstetric anal sphincter injury (3rd or 4th degree tears).

- Need for manual removal of the placenta.

- 5-minute APGAR scores.

- Need for newborn resuscitation.

- Transient fast breathing of the newborn.

- Newborn respiratory distress.

- Newborn death.

- Breastfeeding initiation.

There was a higher risk of the following with waterbirth:

- Cord avulsion (also known as snapping of the umbilical cord after birth, which we will discuss later).

Largest Observational Study on Waterbirth

One of the problems with observational studies is that unlike a randomized trial (when people are randomly assigned to groups), you can’t guarantee that people in the waterbirth group will have similar baseline characteristics to those in the land birth group. For example, it’s expected that people with complications will be asked to “get out of the tub” by the provider, or they might not be offered a water immersion in labor because of risk factors. As a result, waterbirth outcomes are usually better in observational studies—partly because people who end up birthing in water had uncomplicated childbirth experiences.

To address this problem, Bovbjerg et al. (2021) published the largest observational study on waterbirth ever, in which they studied 17,530 waterbirths and 17,530 land births that were matched for more than 80 factors (such as demographics, obstetric history, health conditions, and more). The process they used to match participants, called propensity scoring, resulted in the two groups being as similar as possible at baseline—except that one group was exposed to waterbirth, and the other was not. The researchers only included births that took place at home or in freestanding birth centers, not hospitals.

The Bovbjerg study used a retrospective study design, meaning that researchers looked back in time (“retro”) at medical records to make conclusions. The births they examined came from a data set called the Midwives Alliance of North America Statistics Project (MANA Stats), which collected data on from 2012 to 2018.

Midwives choose to participate in the MANA Stats Project by enrolling clients earlier in pregnancy and collecting data on them all the way through their pregnancy and birth. This is a process called prospective logging, which protects against a type of bias called selection bias. Selection bias happens when the study staff hand pick who they want in each group, based on what they hope the study to show. Selection bias did not occur in this study, because midwives were not allowed to select clients with only good waterbirth outcomes.

To further protect against selection bias, Bovbjerg et al. did not include anyone who was transferred to the hospital during labor. This decision was made because it was unlikely that those transferring to the hospital would be good candidates for waterbirth. Also, if they had included people with transfers during labor, this would have tilted the results in favor of waterbirths at home (because people who transfer and have a hospital land birth typically do so for medical reasons).

The propensity score matching worked—both the waterbirth and land birth groups were quite similar at baseline. About 95% of all participants were married or partnered, 49% had a college degree or higher, 23-24% were eligible for Medicaid, 73-74% had a home birth, 26-27% had a freestanding birth center birth, 72-73% were cared for by a certified professional midwife, 86-87% were white, 26-27% were giving birth to their first baby, and 4% were planning a vaginal birth after Cesarean (VBAC). The average age of participants was 31 years, and the average gestational age at time of birth was 40 weeks 0 days.

The waterbirth group experienced the following positive outcomes (see Table 3):

- Lower rates of postpartum hemorrhage.

- Fewer postpartum transfers to the hospital.

- Fewer postpartum hospitalizations for birthing people.

- Lower rate of severe perineal tears (3rd or 4th degree tears).

- Fewer newborn transfers to the hospital.

- Fewer cases of newborn respiratory distress syndrome.

- Fewer newborn hospitalizations.

There was a lower rate of newborn death in the waterbirth group—0.28 deaths per 1,000 deliveries compared to 0.51 deaths per 1,000 deliveries in the land birth group.

The only negative effects seen with waterbirth were higher rates of umbilical cord avulsion or tearing (sometimes called an umbilical cord snap) (0.57% vs. 0.37%) and higher rates of postpartum uterine infections (0.31% vs. 0.25%). But neither of these resulted in higher hospitalization rates for birthing people or babies, and none of the cases of umbilical cord avulsion resulted in death.

There were no differences between waterbirth and land birth groups in the rate of NICU admissions in the first 6 weeks, or in rates of newborn infections.

Table 3: Benefits and Risks of Waterbirth in the Largest Observational Waterbirth Study to Date by Bovbjerg et al. (2022)

Observational Study on Planned Waterbirths that Become Land Births

Laboring people who are planning a waterbirth may get out of the pool due to personal preference, or because of medical reasons including:

- The midwife or physician may have concerns with the fetal heart rate,

- The birthing person may need pain medication, OR

- Labor may be progressing unusually slow.

In 2016, Bovbjerg et al. published the first study that compared actual waterbirths, intended waterbirths (that ended up being land births), and intended land births.

The study included data from 18,343 midwife-attended births in the U.S. between 2004 and 2009, with 97.6% of births occurring at homes and birth centers. In this study, there were 6,534 waterbirths, 10,290 land births, and 1,573 intended waterbirths that ended up as land births.

Like other researchers, Bovbjerg et al. (2016) found that waterbirth did not appear to increase the risk of bad health outcomes for newborns. In fact, babies born in the water had better health outcomes than babies born on land. The group that fared the worst were those who intended to have waterbirths but left the pool before giving birth. This left the lowest-risk people in the waterbirth group, who had the best outcomes on average.

Since people who birth in water are usually doing well, they (and their newborns) are more likely to have better results. Another way to look at these research results that the U.S. midwives in this study showed good judgment by assessing risk and getting people with complications out of the tub as needed.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a method of research that involves using rich, in-depth data (from interviews or written text) to describe experiences, understand phenomena, and/or look for meaning.

A meta-synthesis is when researchers combine multiple qualitative studies to look for common themes. So far, there have been two meta-syntheses of qualitative studies on waterbirth.

Clews et al. (2020) Meta-Synthesis

In this article, researchers reviewed five qualitative studies that interviewed a total of 30 self-identified birthing women from five different countries. While examining the research, four common themes emerged:

- A knowledge of waterbirth led participants down the path to choosing waterbirth. They learned about waterbirth from books, online articles, and YouTube videos.

- A desire for physiological birth came from feeling that land births did not meet their needs and desires. The participants wanted a more natural or holistic experience. Their decision to get in or out of the water was based on what their body needed. They also felt an instinctive connection with water as soothing and pleasurable.

- Autonomy and control were important. Women reported feeling more in control and increased coping with labor in water. They reported it was easier to avoid interventions they’d had in past births (such as amniotomy, episiotomy, Pitocin®, or the lithotomy birth position with feet in stirrups). They said that the water and tub created a natural barrier that allowed them more privacy and security—nobody could touch them unless they consented to being touched! They also hoped that waterbirth would help them avoid perineal tears.

- An easier transition during the emergence of the baby was meaningful. The mothers felt that their babies were not as shocked when they were birthed from the warmth of the amniotic fluid in the uterus into the warmth of the water of the tub.

The researchers in this study concluded:

“All individuals involved in the care of women during childbirth – from policy makers to midwives – should understand the possibility for waterbirth to offer some women a positive experience and memories of childbirth.”

Large Meta-Synthesis by Reviriego-Rodrigo et al. (2023)

In this study, researchers included 13 qualitative studies from eight countries published between 2013 and 2019. Most of the studies included both water immersion during labor and waterbirth, while some reported only waterbirth findings.

The researchers found four themes across all the qualitative studies:

- Reasons for choosing waterbirth included personal preferences plus knowledge of evidence-based information. Participants were looking for a birth method that would increase relaxation, lower anxiety, decrease pain, increase comfort and well-being, and give them a better chance at a natural birth. They were also interested in a lower chance of perineal tears and a shorter labor. Participants believed that the evidence so far shows no increased risk to babies regarding infection or mortality.

- Perceived benefits of water immersion included more autonomy and control, a higher chance of unmedicated birth, a method of pain relief that doesn’t require interventions, an easier transition into parenthood, mobility and buoyancy in the water, peace/relaxation, improved breathing, privacy, avoiding Pitocin®, and having a positive childbirth experience.

- Perceived barriers of water immersion included safety concerns from vaginal birth after Cesarean (VBAC), pregnancy or labor complications, and a lack of support from family or health care workers.

- Perceived factors that made it possible for them to have a waterbirth included having available tubs and policies that were clear and consistent about who is eligible, support from health care workers trained in waterbirth, clear/accurate information about benefits and risks to aid in decision making, and a culture of respect for waterbirth as a valid option.

Case Reports

The other type of evidence that we have on newborn outcomes after waterbirth comes from case reports. Case reports are published documents about a rare medical event, and they are considered the lowest level of research evidence.

The main advantage of case reports is that they give us information about rare side effects. But the main drawback is that since they only discuss one or two events, we cannot use this evidence to determine how often these events occur. Most case reports are not peer reviewed (some are simply written as letters to the editor), and they often lack enough detail to get a clear picture of what really happened.

In 2020, Vanderlaan and Hall published a systematic review of all the case reports that have ever been published in English about poor newborn outcomes after waterbirth or water immersion during labor. The purpose of their review was to highlight patterns that can be addressed to make waterbirth safer.

The review identified 35 articles with total of 48 cases of poor newborn outcomes (43 events with waterbirth; 11 of which were minor conditions that resolved quickly). Only 14 of the case reports were published in the previous ten years—and so most of the articles did not reflect current waterbirth protocols.

The cases reported difficulty breathing (24 cases), infection (18 cases), and cord avulsion (8 cases). There were seven newborn deaths reported—five due to infection, and two due to unknown causes. Most case reports did not describe the pregnancies, labors, or protocols followed during the water immersion.

The five patterns that the authors reported included:

- Importance of preventing exposure to waterborne pathogens, or water-borne bacteria that can cause illness:

- Specific bacteria that could be dangerous include Legionella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

- These bacteria do not typically cause infection after land births, but 12 cases of infection have been reported after waterbirths.

- Waterbirth providers should ensure a clean water supply and use strict cleaning protocols.

- Water aspiration, or accidental breathing in of water, is not as common as opponents of waterbirth claim:

- Eleven case reports described newborn water aspiration, but seven of these cases were misdiagnosed and should have been labeled as transient tachypnea of the newborn.

- Transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN) is defined as a temporary delay in clearing out the birth fluids from the lungs. This condition occurs in 5.7 out of every 1,000 land births at term.

- Because TTN can happen in any newborn, it makes sense that it would sometimes be seen in newborns after waterbirth.

- Out of the 48 case reports, only a single confirmed case of true water aspiration was reported, and in this case the newborn was dropped in the water, after birth, where it remained for an unreported amount of time.

- Cord avulsion, or a snapping or tearing of the umbilical cord, is a potential risk at any delivery, however research demonstrates that it occurs more frequently in waterbirth than land birth.

- There were eight cases of umbilical cord avulsion after waterbirth, and seven were identified and managed quickly (by immediately clamping the cord), leading to no adverse health effects.

- The one case that was not treated quickly did lead to the baby experiencing temporary anemia (a problem of not having enough hemoglobin in red blood cells to carry oxygen to body tissues). This case report was published in 2000 and as a result, protocols were developed and implemented to 1) prevent cord avulsion and 2) identify and clamp the cord quickly if it does happen.

- It’s important to follow current waterbirth practice guidelines:

- There were eight case reports that suggest the provider was not trained in safe waterbirth practices.

- Examples of unsafe practices included: 1) permitting a waterbirth even though there were signs of complications such as thick meconium in the amniotic fluid or maternal fever, 2) using hot tubs or home bathtubs (which increase the risk of bacterial growth due to recirculating water in the jets), and 3) keeping the tub filled with warm water for two weeks leading up to the birth (again increasing the risk of infection due water that could be fostering bacterial growth).

- Three case reports included newborn hyponatremia, or low blood sodium levels.

- The authors propose that over hydration (drinking too much water) and staying in the tub for many hours could potentially increase the risk of the birthing person having low blood sodium levels.

- The low blood sodium levels in the birthing person could then lower the baby’s sodium levels at birth.

- This is an area that needs more research.

What can we learn from these case reports?

If you read the individual case reports, most of the authors do not recommend a ban on waterbirths. Instead, they make recommendations to improve safety and informed consent. Some of their recommendations are:

- Pseudomonas can be found in water supplies both in hospitals and in the community, and it can cause severe infections in newborns.

- Plastic tubing is the perfect environment for Pseudomonas to grow, especially if the strain of bacteria is resistant to disinfectants (Vochem et al. 2001).

- Providers who offer waterbirth in facilities may want to take frequent cultures from the birthing pool system or after each water birth, shorten the length of filling and exit hoses, and heat disinfect hoses after each use (Rawal et al., 1994).

- Many home birth providers, because of these case study findings, now require their clients to use brand new hoses to fill up a home birthing pool.

- Hospitals should track waterbirth outcomes and have policies in place to prevent infections, such as pool maintenance, decontamination, and universal precautions (Franzin et al. 2004).

- As part of the educational process, inform families who are interested in waterbirth that it is important that they not re-submerge the baby in the water after it has reached the air (Vanderlaan et al. 2020).

- Caution should be used if a birthing person with a recent diarrheal illness is considering a waterbirth (Soileau et al. 2013).

- Spa-like pools with a heater and a re-circulation pump contain complex plumbing that can promote the growth of bacteria and be difficult to disinfect. The environment is especially risky when the tubs are filled in advance of labor and held at a warm temperature. In contrast, a rigid or inflatable tub that is filled at the start of labor poses less risk for bacterial infections (Collins et al. 2016).

Overall Summary of the Pros and Cons

Based on the research studies we’ve reviewed above, here is our summary of the pros and cons of waterbirth.

Pros of Waterbirth

Waterbirth is protective of normal vaginal birth, and can increase the chance of having a faster, less complicated birth. Researchers have found evidence from randomized trials that planning for a birth in water can lead to shorter labors, less need for Pitocin®, and lower rates of giving birth via cesarean or with forceps/vacuum (Caichian et al. 2009; Ghasemi et al. 2013; Gayiti et al. 2015).

Waterbirth can help protect the perineum (the tissue between the vagina and rectum). Both randomized trials and observational studies have found that waterbirth is associated with a higher rate of intact perineum and lower episiotomy rates (Chaichian et al. 2009; Gayiti et al. 2015; Burns et al. 2022). In addition, the largest observational study found that waterbirth is associated with a lower rate of severe perineal tears (3rd or 4th degree lacerations) (Bovbjerg et al 2021).

Waterbirth has been consistently shown to decrease pain in labor. As a result, waterbirth also leads to less use of epidurals and injectable opioids for pain relief during childbirth (Nikodem 1999; Chaichian et al. 2009; Ghasemi et al. 2013; Gayiti et al. 2015; Burns et al. 2022). There is nothing wrong with having an epidural or pain medication during labor—but some birthing people wish to avoid these interventions for personal reasons, or because of potential side effects. Planning a waterbirth can be an effective tool to help families reach their pain management goals. And if water immersion does not provide enough pain relief, then the birthing person can switch to a land birth with pain medications.

Waterbirth is associated with improved health outcomes for birthing people, including lower rates of postpartum hemorrhage and maternal infection (Burns et al. 2022). Observational research has shown that people who have waterbirths at home are less likely to be transferred to the hospital postpartum than their peers who have land births at home (Bovbjerg et al. 2021). In addition, research has consistently shown that waterbirth results in higher birth satisfaction. In qualitative studies, birthing people have described feeling more in control in water, and that water created a natural barrier that helped them feel more safe, private, and secure (Clews et al. 2020; Reviriego-Rodrigo et al. 2023).

Waterbirth is also associated with positive health outcomes for babies. The largest, highest-quality observational study on waterbirth found that babies born via home waterbirth were less likely to be transferred to the hospital, less likely to have newborn respiratory distress syndrome, less likely to be hospitalized, and had a lower mortality rate compared to babies born at home via land birth (Bovbjerg et al. 2021). In addition, one randomized trial found that waterbirth led to a substantially lower risk of meconium in the amniotic fluid, as well as better Apgar scores at birth (Ghasemi et al. 2013). We do not know exactly why these outcomes are better with waterbirth. It’s possible that waterbirth may affect newborn health because of the increased likelihood of a smoother birth with fewer interventions and complications. There may also be better outcomes because only the lowest risk babies are born in water—when there are signs of potential complications, the birthing person is usually asked to get out of the tub.

Cons of Waterbirth

Waterbirth leads to a higher risk of newborn cord avulsion, or snapping. With waterbirths, the baby might be lifted out of the water too quickly, and this might cause the umbilical cord to snap, especially if there is an abnormally short cord. The largest analysis on this subject (Bovbjerg et al. 2021) found a rate of 4.1 cord avulsions per 1,000 waterbirths vs. 1.3 cord avulsions per 1,000 land births. The signs of cord avulsion in a waterbirth can include a dramatic change in the color of the water to deep red, a snapping sound, sudden release of cord tension, seeing the cord snap, and/or signs of the newborn going into shock from losing too much blood. If the cord snaps, someone should immediately clamp the newborn’s end of the umbilical cord and assess the newborn for signs of shock. Researchers do not consider cord avulsion an emergency for a skilled provider, because as long as the cord avulsion is recognized and the cord immediately clamped, then complications can be avoided.

Cord avulsion can be prevented by bringing the baby to the surface gently, assessing cord length/tension at birth, and not excessively pulling on the cord. In a five-year study that took place in eight institutions (Sidebottom et al. 2022), researchers documented three cases of waterbirth-related cord avulsion in the first year. After these cord avulsions occurred, staff were educated on how to prevent cord avulsion, and there were zero cases of cord avulsion during the next four years.

Overall rates of newborn infection do not differ between waterbirth and land birth (Bovbjerg et al. 2021). However, there have been reports of rare cases of newborn infection after waterbirth (Vanderlaan & Hall 2020). Birth attendants and hospital staff should follow evidence-based guidelines for preventing waterborne infection transmission such as using tubs that are easy to disinfect (and avoid tubs with pipes that recirculate water), filling tubs closer to the time of the birth (avoid long-standing water), and regularly testing the hospital water supply, hoses, and birthing pools (Nutter et al. 2014b).

The largest and highest-quality meta-analysis on waterbirth did not find any increase in maternal infection with waterbirth (Burns et al. 2022). However, the largest observational study on waterbirth (Bovbjerg et al. 2021) reported a slightly higher rate of uterine infection in the first six weeks after a waterbirth (0.31% vs. 0.25%). It is important to note that they reported no increase in the risk of hospitalization, indicating that these uterine infections were successfully treated with antibiotics at home. This is an area that needs further research.

A temporary delay in clearing birth fluids from the lungs (transient tachypnea of the newborn) can occur in babies born on land or in water. There does not seem to be any higher risk of transient tachypnea with waterbirth (Bovbjerg et al. 2021). However, most providers who attend waterbirths recommend that a birth take place on land if there are signs that a fetus may be more likely to experience complications. These signs may include non-reassuring fetal heart tones, maternal fever, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, suspected fetal growth restriction, or other risk factors (Nutter et al. 2014b). If a provider trained in waterbirth asks you to get out of the tub, this is because they believe a waterbirth would not be safe in your case.

Waterbirth cannot be combined with some interventions, including epidurals/spinals and injectable opioids for pain management. If you were hoping for a waterbirth, but these interventions are needed or chosen, then you will need to switch to a land birth (Nutter et al. 2014b). Some hospitals do not permit waterbirth if you need Pitocin® for labor induction or augmentation, while others do (Personal communication, J. Anderson, 2023).

Although most people find water immersion in labor pleasurable, it is possible that you may change your mind and want to get out of the tub. In one survey study from England, a small number of participants said that they got cold, or the baby got cold, that their contractions went away, or that staff were not supportive (Richmond 2003).

It is important that the water temperature is assessed at least every hour, because maintaining the water temperature between 37 to 38 degrees Celsius (98.6 to 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit) helps prevent the baby from experiencing hypothermia or hyperthermia (too low or too high body temperature) (Nutter et al. 2014b).

Sometimes people ask us if waterbirth influences the newborn microbiome. The only study we found on waterbirth and the newborn microbiome did not show any difference in the newborn microbiome between babies born via water vs. land; however, more research is needed (Fehervary et al. 2004).

Healthy babies have a dive reflex that prevents them from taking their first breath until they are exposed to air. A baby being born underwater must be born fully underwater and not exposed to cooler temperatures or air until after their face is brought to the surface. Once the baby’s face is in the air, then their lower body and extremities should rest in the warm water to help keep their body warm. If a birthing person stands up mid-birth, and the baby’s face/skin is exposed to the air, then the birthing person should not squat back down and re-immerse the baby’s head in the water (Nutter et al. 2014b).

The dive reflex can be overridden if a baby is experiencing distress—this may cause a newborn to prematurely gasp underwater before they surface. This is another reason why providers skilled in waterbirth watch to make sure there are no signs of complications before proceeding with a waterbirth (Nutter et al. 2014b).

Professional Guidelines

In the past, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have published joint guidelines that denounced and discouraged waterbirth. Their strongly worded 2014 guidelines were not based on research evidence, but mainly on opinion and case reports. In 2016, the AAP and ACOG softened their stance on waterbirth and began to discuss the concept of informed consent. We reviewed the influential 2014 and 2016 AAP/ACOG guidelines on waterbirth here.

In 2022, the AAP released a new statement by Nolt et al. called, “Risk of Infectious Diseases in Newborns Exposed to Alternative Perinatal Practices.” In this latest statement, the authors relied heavily on a meta-analysis by Edwards et al. (2023) that only reviewed six randomized, controlled trials (with a total of 709 participants) and excluded all observational studies (see Table 1 to compare the Edwards et al. meta-analysis to other meta-analyses on waterbirth).

The AAP also mentioned several case reports about Pseudomonas and Legionella infection. In contrast, they never discussed or cited any of the high-quality meta-analyses or large observational studies that we have reviewed in this EBB article. Their opinion was, “Families should be cautioned against water birth during and past the second stage of labor, in the absence of any current evidence to support maternal or neonatal benefit, and with reports of serious and fatal infectious outcomes in infants.” As long as the AAP retains their bias against waterbirth, it is likely that they will continue to ignore the many peer-reviewed studies that have been published on waterbirth. Unfortunately, the AAP’s continued recommendation against waterbirth means that many hospitals will continue to have official or unofficial “bans” on waterbirth. For many families, the only way they can access waterbirth is through home birth or a freestanding birth center.

In contrast to the AAP, the American College of Nurse Midwives (2014), the American Association of Birth Centers (2014), the Royal College of Midwives, and the New Zealand College of Midwives (2019) have all released statements endorsing waterbirth as a safe, evidence-based option.

Practical guidelines for clinicians who support waterbirth have been published by the American College of Nurse Midwives (2017), the University Hospital Wishaw (2020) in Scotland, University Hospitals of Leicester (2021) in England, and the National Health Service in Wales (2022).

In 2014, Dr. Nutter, Dr. Shaw-Battista, and Dr. Marowitz of the U.S. published a paper called, “Waterbirth Fundamentals for Clinicians” that includes practical principles for waterbirth, clinical wisdom, and advice for implementing waterbirth in hospitals. The free appendix of their paper includes a waterbirth consent form and clinical guidelines for water immersion in labor and waterbirth.

The bottom line

New research evidence on waterbirth is continuing to emerge! For birthing people, there are benefits associated with waterbirth. There is strong evidence that waterbirth is associated with a lower episiotomy rate, and that planning a waterbirth leads to higher rates of having an intact perineum. People who have waterbirths are less likely to need pain medicine for pain relief compared with people who give birth on land. Waterbirth parents also report higher levels of satisfaction with pain relief and with their experience of childbirth. Some of the benefits of waterbirth (such as decreased pain during the first stage of labor) can also be achieved from using water immersion during labor, before the birth.

Evidence also shows that waterbirth can be safe for babies. The largest and highest-quality meta-analysis on waterbirth found that newborns born via waterbirth had similar health outcomes than babies born on land (Burns et al. 2022). In the single largest study on waterbirth so far, they found that babies in the waterbirth group had better outcomes than those in the land birth group (Burns et al. 2021). This may be partly because waterbirth are associated with faster, easier, less complicated births, and partly because parents experiencing complications are asked to get out of the tub (leaving the healthiest babies in the waterbirth group).

The main waterbirth complication for newborns is umbilical cord avulsion, which occurs in about 4 per 1,000 waterbirths. Simple steps can be taken to prevent cord avulsion, and treat it quickly, if it occurs.

Based on the evidence from many research studies—including randomized trials, large observational studies, and meta-analyses—current evidence suggests that waterbirth is a safe option for families. If you are having a low-risk pregnancy and birth, have a desire for an unmedicated, low-intervention birth, and there are experienced staff who are trained in attending waterbirths, then evidence supports this birth method.

Unfortunately, there are still very few hospitals (outside of the United Kingdom) that provide waterbirth as an option—and in fact, many hospitals “ban” waterbirth. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ negative opinion statements on waterbirth have had a negative influence on the availability of waterbirth in many hospitals. However, it is important to remember that the AAP’s recommendations against waterbirth are not based on the best evidence and should be challenged.

If you are interested in waterbirth, find out which facilities nearby provide waterbirth, and make sure you understand hospital policy. Here at EBB, we have witnessed false advertising—where a hospital advertises that they have waterbirth (to take advantage of the popularity of this option), but in fact do not permit it. If your hospital or hospital-based provider says they provide waterbirth, you can ask the following questions:

- How many birthing rooms have tubs? Are all the tubs functioning? What are the chances that I can get a room with a tub?

- Do you require parents to get out of the tub during the pushing phase? Can the baby be born in the water? [This question helps clarify whether they permit water immersion during labor only and then make you get out for the birth].

- What training do your staff have in caring for parents during waterbirth? What training do they have in managing complications during a waterbirth?

- What are some reasons that I might be asked to get out of the tub? What is your preference for where I birth the placenta?

- Out of the last 10 clients of yours who said they wanted a waterbirth, how many of them gave birth in the water?

- If I need continuous fetal monitoring, do you have wireless, waterproof monitors that can be worn in the tub?

- What infection control measures are in place for waterbirth?

If waterbirth is a high priority for you, and your chosen facility does not support waterbirth, you may want to consider looking at other birth options in your community. Or you could plan to take advantage of water immersion in labor (before the pushing phase), as this also offers many benefits. You are encouraged to print off a copy of the 1-page handout that goes along with this article, to help educate your providers.

Ultimately, as more parents, health care workers, and birth workers request waterbirth and share the evidence, more facilities will begin to provide midwifery-led, evidence-based options—like waterbirth—for families who desire this birth option.

References:

- Allen, J., Gao, Y., Dahlen, H., et al. (2022). “Is a randomized controlled trial of waterbirth possible? An Australian feasibility study.” Birth 49(4): 697-708.

- American College of Nursing. (2017). “A model practice template for hydrotherapy in labor and birth.” J Midwifery Womens Health, 62(1): 120-126.

- Bovbjerg, M. L., Cheyney, M., Everson, C. (2016). “Maternal and newborn outcomes following waterbirth: The Midwives Alliance of North America statistics project, 2004 to 2009 cohort.” J Midwifery Womens Health, 61(1): 11-20.

- Bovbjerg, M. L., Cheyney, M., Caughey, A. B. (2021). “Maternal and neonatal outcomes following waterbirth: A cohort study of 17,530 waterbirths and 17,530 propensity score-matched land births.” BJOG 129: 950-958.

- Burns, E. E., Boulton, M.G., Cluett, E., et al. (2012). “Characteristics, interventions, and outcomes of women who used a birthing pool: a prospective observational study.” Birth 39(3): 192-202.

- Burns, E., Feeley, C., Hall, P. J. (2022). “Systematic review and meta-analysis to examine intrapartum interventions, and maternal and neonatal outcomes following immersion in water during labour and waterbirth.” BMJ Open 12:e056517.

- Chaichian, S., Akhlaghi, A., Rousta, F., et al. (2009). “Experience of water birth delivery in Iran.” Arch Iran Med 12(5): 468-471.

- Clews, C., Church, S., Ekberg, M. (2020). “Women and waterbirth: A systematic meta-synthesis of qualitative studies.” Women Birth 33(6): 566-573.

- Cluett, E. R., Burns, E., Cuthbert, A. (2018). “Immersion in water during labour and birth.” Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 5(5): CD000111.

- Collins, S. L., Afshar, B., Walker, J. T., et al. (2016). “Heated birthing pools as a source of Legionnaires’ disease.” Epidemiol Infect, 144(4): 796-802.

- Davies, R., Davis, D., Pearce, M., et al. (2015). “The effect of waterbirth on neonatal mortality and morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep, 13(10): 180-231.

- Edwards, S., Angarita, A. M., Talasila, S., et al. (2023). “Waterbirth: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Am J Perinatol. Online ahead of print.

- Fehervary, P., Lauinger-Lorsch, E., Hof, H., et al. (2004). “Water birth: microbiological colonisation of the newborn, neonatal and maternal infection rate in comparison to conventional bed deliveries.” Arch Gynecol Obstet 270(1): 6-9.

- Franzin, L., Cabodi, D., Scolfaro, C., et al. (2004). “Microbiological investigations on a nosocomial case of Legionella pneumophila pneumonia associated with water birth and review of neonatal cases.” Infez Med 12(1): 69-75.

- Fritschel, E., Sanyal, K., Threadgill, H., et al. (2015). “Fatal legionellosis after water birth, Texas, USA, 2014.” Emerg Infect Dis, 21(1): 130-132.

- Gayiti, M. R., Li, X. Y., Zulifeiya, A. K., et al. (2015). “Comparison of the effects of water and traditional delivery on birthing women and newborns.” Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 19(9): 1554-1558.

- Ghasemi, M., Tara, F., and Ashraf, H. (2013). “Maternal-fetal and neonatal complications of water-birth compared with conventional delivery.” [Persian]. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil 16:9-15.

- Nikodem, C. (1999). “The effects of water on birth: A randomised controlled trial.” Rand Afrikaans University.

- Nolt, D., O’Leary, S. T., Aucott, S. W.; American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Infectious Diseases; AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn. (2022). “Risk of infectious diseases in newborns exposed to alternative perinatal practices.” Pediatrics 149(2): e202105554.

- Nutter, E., Meyer, S., Shaw-Battista, J., et al. (2014a). “Waterbirth: an integrative analysis of peer-reviewed literature.” J Midwifery Womens Health 59(3): 286-319.

- Nutter, E., Shaw-Battista, J., Marowitz, A. (2014b). “Waterbirth fundamentals for clinicians.” J Midwifery Womens Health 59(3): 350-354.

- Reviriego-Rodrigo, E., Ibargoyen-Roteta, N., Carreguí-Vilar, S. (2023). “Experiences of water immersion during childbirth: A qualitative thematic synthesis.” BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23: 395.

- Richmond, H. (2003). “Women’s experience of waterbirth.” Pract Midwife 6(3): 26-31.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists/Royal College of Midwives (RCOG/RCM 2006). “Joint statement No. 1: Immersion in water during labour and birth.”

- Shaw-Battista, J. (2017). “Systematic review of hydrotherapy research: Does a warm bath in labor promote normal physiologic childbirth?” J Perinat Neonat Nurs 31(4): 303-316.

- Soileau, S. L., Schneider, E., Erdman, D.D., et al. (2013). “Case report: severe disseminated adenovirus infection in a neonate following water birth delivery.” J Med Virol 85(4): 667-669.

- Taylor, H., Kleine, I., Bewley, S., et al. (2016). “Neonatal outcomes of waterbirth: a systematic review and meta- analysis.” Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 101(4): F357- 365.

- Vanderlaan, J., Hall, P. J., and Lewitt, M. (2018). “Neonatal outcomes with water birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Midwifery. 59:27-38.

- Vanderlaan, J., and Hall, P. (2020). “Systematic review of case reports of poor neonatal outcomes with water immersion during labor and birth.” J Perinat Neonat Nurs 34(4): 311-323.

- Vochem, M., Vogt, M., and Doring, G. (2001). “Sepsis in a newborn due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa from a contaminated tub bath.” N Engl J Med 345(5): 378-379.

- Woodward, J. and Kelly, S. M. (2004). “A pilot study for a randomised controlled trial of waterbirth versus land birth.” BJOG 111(6): 537-545.

Resources:

- Evidence Based Birth® Podcast Episodes:

- The ACNM created a two-page handout on waterbirth, written for families. To access this printer- friendly PDF handout, click here.

- In the process of writing the original version of this article, I purchased several waterbirth books. By far, the most evidence-based book that I read was Dianne Garland’s “Revisiting Waterbirth: An Attitude to Care.” It was originally written for midwives, but expecting parents may also find this book helpful.

- Several organizations offer trainings for birth attendants and hospitals who want to offer waterbirth during labor and birth or improve their current practices:

- GynZone: Visit https://gynzone.com/online-courses/waterbirth/

- Waterbirth International: Visit https://waterbirth.org

- Waterbirth Works: Visit https://nuttercnm.thinkific.com/courses/waterrbirthworks

Acknowledgments:

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Liz Nutter, DNP, ARNP, CNM, FACNM, and Jennifer Anderson, RN, BSN for reviewing the 2024 update of this article. We would like to thank the clinician experts who helped with the original 2014 Waterbirth article: Dr. Robert Modugno, MD, MBA, FACOG; Angela Reidner, RN, MS, CNM; and Barbara Harper, RN, Director of Waterbirth International. In 2018 we also received help from Dr. Jette Aaroe Clausen, Ph.D, Senior Lecturer at Metropolitan University College, and Mehry Basati, Iranian midwife and student at Metropolitan University College, who translated key details from the Ghasemi et al. 2013 randomized trial [Persian] into English.

We are thankful for your support!

All Evidence Based Birth® Signature Articles are publicly available on our website for free.

We are able to continue providing this information, thanks to the support of our Professional Members:

If you would like to help support our work, please consider becoming an Evidence Based Birth® Professional Member. Our Professional Members get access to printable versions of our Signature Articles, 24+ hours of continuing education courses, monthly online trainings, a private community, and more!

Stay empowered, read more :

EBB 310 – Doulas & Nurses Advocating Together for Positive Shifts in Birth Culture with Joyce Dykema, EBB Instructor & Brianna Fields, RN

Don't miss an episode! Subscribe to our podcast and leave a review! iTunes | Spotify | YouTube Dr. Rebecca Dekker is joined by Joyce Dykema, doula and EBB Instructor, and Brianna Fields, a labor and delivery nurse, to discuss advocating for positive shifts in...

EBB 308 – The Intersection of Environmental Justice and Midwifery Care with Dr. Tanya Khemet Taiwo

Don't miss an episode! Subscribe to our podcast and leave a review! iTunes | Spotify | YouTube Curious which toxins should be most avoided for people of reproductive age and their children? In this episode, Dr. Tanya Khemet Taiwo, LM, CPM, MPH, PhD unravels the...

EBB 307 – Unexplained Infertility, Endometriosis, and a Birth Center Birth Story with Ellora La Shier, EBB Childbirth Class Graduate

Don't miss an episode! Subscribe to our podcast and leave a review! iTunes | Spotify | GoogleIn this episode, Ellora La Shier, graduate of the EBB Childbirth Class, shares about her struggle with six years of unexplained infertility and how it impacted her...